Cinecolor Corporation came into being in 1932 as a result of the financial failure of Multicolor Corp. Technicolor and Multicolor were, by far, the two most successful two-color processes throughout the late 1920s. Technicolor probably survived because Herbert Kalmus was able to get more and more money from investors despite the company showing little or no profit for its first 15 years of existence. Cinecolor took the Multicolor system and continued to use it with little or no modification until the late 1940s when Eastman color negative and Ansco color made it possible to obtain three color photographs without the use of the Technicolor three strip camera.

Unlike the Technicolor two-color processes which photographed both color elements on the same piece of black and white negative, Cinecolor used two films in "bi-pack", meaning that two films were placed emulsion to emulsion. Each film was sensitized and/or filtered to record its appropriate portion of the color spectrum, red or green. Film used in the Cinecolor process was supplied by Eastman Kodak or DuPont. Essentially, any camera capable of handling bi-pack negatives could be used to photograph a Cinecolor film, though some special film movements were made specifically for the task.

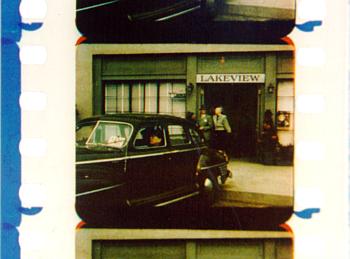

Seen at right is a Bell & Howell bi-pack camera used to produce two-color films such as Cinecolor. The camera could also be used for other bi-pack requirements. It is doubtful that this type of camera ever filmed a scene inside the interior of an automobile.

Photo courtesy Jan-Eric Nyström

Click on the illustration at right to view a 1931 full page ad for Bell & Howell's bi-pack setup.

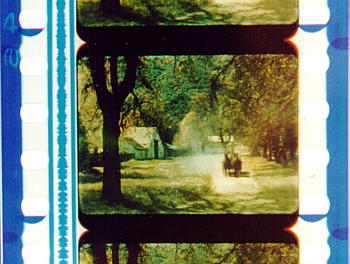

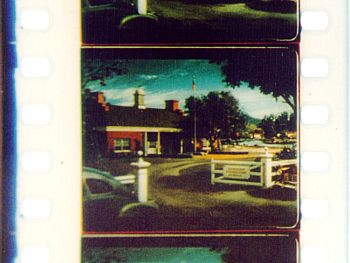

The Cinecolor two-color print carried its two color components on opposite sides of the film. To make this print, a special "duplitized" stock was used which had a yellow dye layer beneath the emulsions. A step printer placed the printing stock between the two color component negatives and both sides of the stock were exposed simultaneously. The sound track was also printed at this time on the blue-green side of the film. After conventional developing the print carried a black & white image on both sides of the film.

The second step of producing a color image requires that the film be floated on a chemical bath that converts the red record, in contact with the bath, to a blue-green complementary tone. The film is then dried and the process is repeated on the opposite side of the film using chemicals that convert the green image to a red-orange tone. The Cinecolor process is relatively complex, relying heavily on chemical reactions to create the image, and this brief explanation is presented to provide only a basic understanding of how it worked.

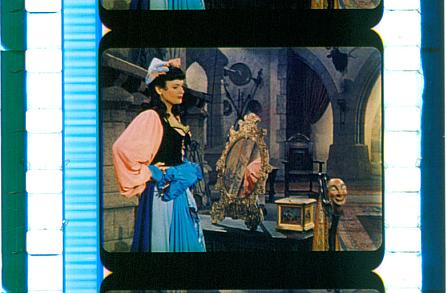

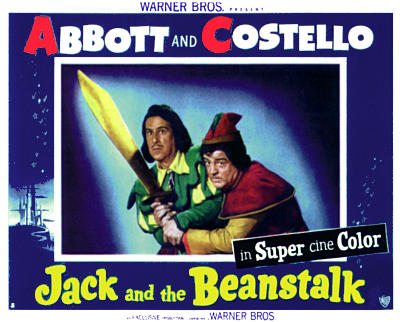

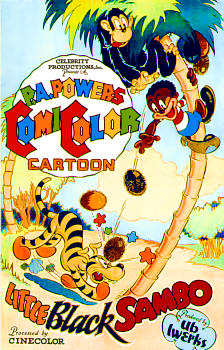

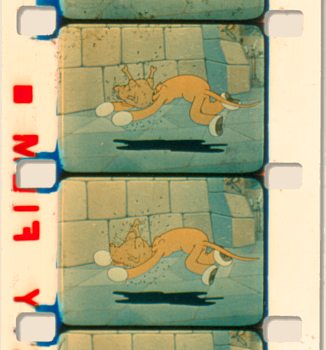

From 1932 to 1940, Cinecolor was used solely for short subjects, primarily from the smaller studios. The first feature film to use the process was The Gentleman from Arizona, produced by Monogram (later Allied Artists) Pictures. While the major studios used the process from time to time for short subjects, such as Paramount's Popular Mechanix series and Popeye cartoons, the primary customers for the system were Monogram, Producers Releasing Corporation, Screen Guild Productions, Eagle-Lion, and others. Republic Pictures, owners of Consolidated Film Industries, developed a similar system that they called Trucolor. In 1948, when a strike halted production at Technicolor briefly, Warner Bros released several Looney Toon cartoons in Cinecolor. These are probably the most commonly seen examples remaining in circulation today.

From 1932 to 1940, Cinecolor was used solely for short subjects, primarily from the smaller studios. The first feature film to use the process was The Gentleman from Arizona, produced by Monogram (later Allied Artists) Pictures. While the major studios used the process from time to time for short subjects, such as Paramount's Popular Mechanix series and Popeye cartoons, the primary customers for the system were Monogram, Producers Releasing Corporation, Screen Guild Productions, Eagle-Lion, and others. Republic Pictures, owners of Consolidated Film Industries, developed a similar system that they called Trucolor. In 1948, when a strike halted production at Technicolor briefly, Warner Bros released several Looney Toon cartoons in Cinecolor. These are probably the most commonly seen examples remaining in circulation today.

|  film courtesy of Ron Merk |

The resulting two-color print was capable of containing pleasing colors but accuracy was hardly more possible than with any other two-color system. Great care was taken in original photography to use costumes and set colors that resulted in the desired final hues. Below is a table of some of the color interpretations that Cinecolor and similar bi-pack systems yielded:

| Color of Original | Color Reproduced | |||

| White |  |  | White | |

| Grey |  |  | Grey | |

| Black |  |  | Black | |

| Orange |  |  | Red-Orange | |

| Yellow |  |  | Light Red-Orange | |

| Yellow-Green |  |  | Very pale Orange (Pinkish) | |

| Green |  |  | Grey | |

| Blue-Green |  |  | Green-Blue | |

| Blue |  |  | Deep Green-Blue | |

| Blue-Violet |  |  | Blackish Green-Blue | |

| Violet |  |  | Black | |

| Purple |  |  | Reddish Grey | |

| Rose |  |  | Grey Red-Orange | |

| Flesh Color |  |  | Fairly correct | |

| Foliage |  |  | Grey Blackish-Green | |

| Sky-Blue |  |  | Pale Blue-Green |

Cinecolor resulted in not only a limited palette, it also suffered from other problems that were decidedly inferior to the Technicolor system. Having the color elements on opposite sides of the film resulted in a soft projected image because it was not possible to hold focus on both records at the same time. Whereas Technicolor applied a silver based photographic soundtrack equal to or better than any black & white film, Cinecolor created a cyan or Prussian blue soundtrack on the blue-green side of the film. While it was possible, through the use of special photocells, to obtain acceptable quality soundtracks, the cyan colored track was not especially compatible with sound reproducers that had been used for black & white films. Theatres did not convert their sound systems just to make Cinecolor movies sound better and black & white movies sound worse. Other color processes, both two-color and three-color, have used dye based soundtracks with similar inferior results, including Technicolor for a brief period.