THE ALMOST SECOND CINEMASCOPE FILM THE ALMOST SECOND CINEMASCOPE FILM

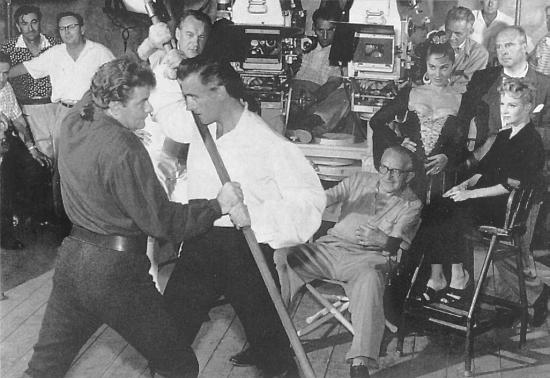

Seen above, pointing, is British cinematographer Jack Cardiff directing Errol Flynn in the film that would have been the 2nd CinemaScope release were it not for Flynn's failure to obtain adequate financing for the project. Cardiff owned a French anamorphic lens and Flynn negotiated with Darryl Zanuck to have Fox distribute his film as a CinemaScope release. Two cameras are partially visible in this photo. We believe that the visible lens is an early Bausch & Lomb adapter. Unfortunately William Tell, which Cardiff directed as well as photographed, was never completed. The footage that was shot has been missing for decades. Jack Cardiff has the distinction of having also shot some of the very earliest Technirama and VistaVision films, as well as being a one of the most gifted pioneers in Technicolor films. Photo courtesy of Jack Cardiff

The Bausch & Lomb Anamorphic Adapter

Current photos of a vintage Bausch & Lomb CinemaScope adapter lens, (20th Century-Fox camera department inventory number 20-181), courtesy of John Whittle.

While the adapter was superceded by the "combination" lens in 1954, they continued to be used throughout the life of CinemaScope production. Due to the small diameter of the rear element, the adapter was useable with only a few focal lengths of the Baltar prime lens. It was necessary to focus the adapter and the prime lens separately, considered to be a significant drawback when focus was changed during a shot.

During the first months following the introduction of CinemaScope, 20th Century-Fox worked with Technicolor in an attempt to install dye transfer printing in the DeLuxe lab. A few films carried a screen credit of "Color by Technicolor-DeLuxe", including Black Widow, King of the Khyber Rifles, and Prince Valiant. Despite the consent decree that made it possible for anyone to utilize Technicolor's technology, DeLuxe abandoned dye transfer in favor of Eastman color print film. Perhaps an economically sound decision but only great care at DeLuxe created high quality prints, and great care was not the norm.

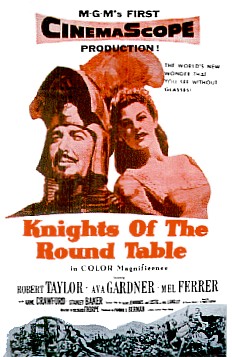

M-G-M's first CinemaScope feature, opening in late 1953, was rather inauspicious, but it was distinguished by a typically excellent music score by Miklos Rozsa, which he wrote and recorded in only six weeks. The reason for the rush to get the music done so quickly? To get Knights of the Round Table into theatres before Fox's similar chain mail epic, Prince Valiant (below right), which was perhaps slightly better, but owed a lot of it's enjoyment to Franz Waxman's epic music, James Mason's wonderful villainy, and the way Janet Leigh filled out her costume.

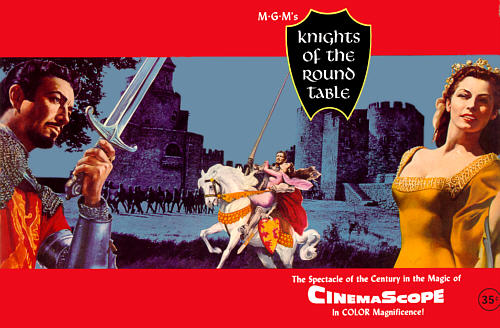

MGM Knights of the Round Table souvenir booklet cover. Despite all the MGM hoopla over CinemaScope, they covered their investment with a simultaneously filmed flat version (see below). Seen at the right, Ava Gardner showing that even though CinemaScope was wide, there was still some of that "coming at you" effect in the "modern miracle you could see without special glasses. "COLOR MAGNIFICENCE"? It certainly wasn't Technicolor. It was inexplicably grainy Eastman Color.

The clever folks at MGM had not yet invented the "Metrocolor" tradename for their lab.

Hedging Bets - Seen at left is an Australian poster for Knights of the Round Table. MGM produced both CinemaScope and conventional "flat" versions of this film and quite a few others during the first months of the new anamorphic revolution. Fox had done the same only with The Robe. While these conventional versions were seldom, if ever, seen in North America, they did get some play in Europe before an adequate supply of anamorphic projection lenses was available and enough theatres had installed the new wide screens. Despite not being in CinemaScope, this version of Knights of the Round Table was also in Color Magnificence. Quite likely Technicolor made the European prints at that time. Hedging Bets - Seen at left is an Australian poster for Knights of the Round Table. MGM produced both CinemaScope and conventional "flat" versions of this film and quite a few others during the first months of the new anamorphic revolution. Fox had done the same only with The Robe. While these conventional versions were seldom, if ever, seen in North America, they did get some play in Europe before an adequate supply of anamorphic projection lenses was available and enough theatres had installed the new wide screens. Despite not being in CinemaScope, this version of Knights of the Round Table was also in Color Magnificence. Quite likely Technicolor made the European prints at that time.

Above we see an action scene from Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer's Moonfleet being simultaneously photographed in CinemaScope and standard flat versions. The flat version was cropped to 1.75:1 ersatz widescreen and shown in theatres outside the U.S. that had not yet installed CinemaScope. MGM called the flat version Metroscope.

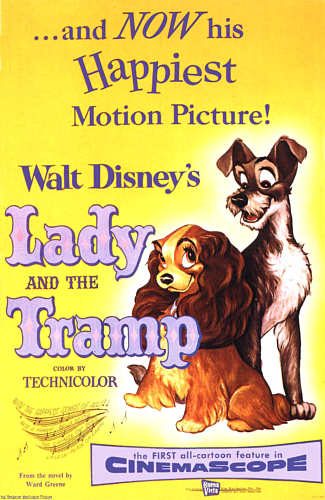

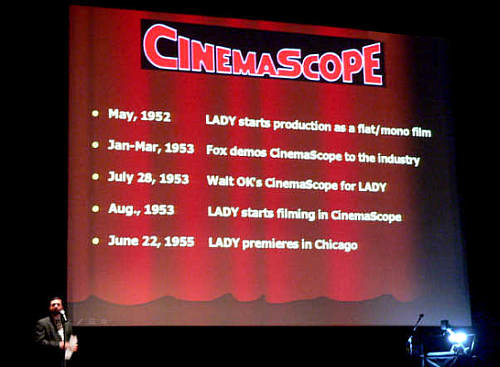

Walt Disney put his animators to work immediately using the new CinemaScope process and created the first animated cartoon in the system, Toot, Whistle, Plunk, and Boom. He also produced the first feature length cartoon, Lady and the Tramp. Like MGM, Disney also hedged his bets on CinemaScope, he had the film photographed in standard Academy format for theatres that did not install the new system. By the time the film was finished, in 1955, CinemaScope had been so universally accepted that the Academy version remained virtually unseen for decades.

In February 2006, the Disney Studios presented a fresh print of Lady at the wonderful El Capitan Theatre in Hollywood. Following the film was a panel discussion where Disney restoration head Theo Gluck presented some history on the film. Also present among the pane was one of our personal favorites, Stan Freberg, who had done voices in the film.

As Theo explained, Lady was virtually complete when Walt Disney decided have the film reshot in CinemaScope. Rather than taking in a wider image than normal, the rephotographed Lady and the Tramp retained the same width in CinemaScope as the original flat photography but substantially less tall.

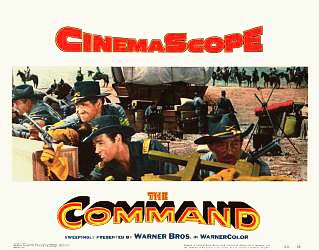

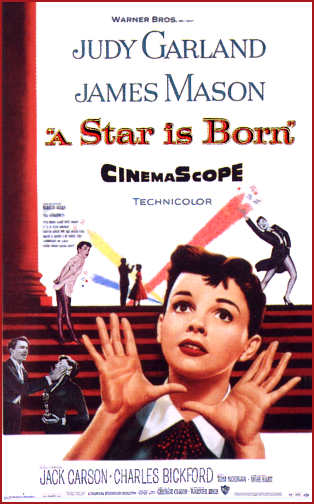

Warner Bros. first real CinemaScope feature was the remake of Selznick's A Star Is Born. The studio had first produced a film called The Command hoping to use Zeiss anamorphic lenses. Warner's had a contract with Zeiss but they had problems and Warners used Vistarama optics, manufactured by the Simpson Optical Manufacturing Company. (More on Vistarama can be found in the "Mayflies" section which you can access from the Lobby page.) The Zeiss camera lens problems appeared insurmountable and Warner's finally signed a contract with Fox for the use of CinemaScope and Bausch & Lomb optics. As part of the agreement, The Command was released under the CinemaScope banner rather than the failed WarnerSuperScope moniker. Fox bought out Warner's lens contract with Zeiss and put the German lens maker to work improving their design for projection lenses, which were in short supply. It is entirely possible that Zeiss ultimately may have produced some of those lenses with Bausch & Lomb labelling. The Command certainly would not qualify as an auspicious introduction for any process (it was also shot in 3-D), and it got the dreadful Warnercolor treatment. A Star Is Born, which was a truly big budget film, directed by George Cukor, was given enough money to let Technicolor do the lab work and printing.

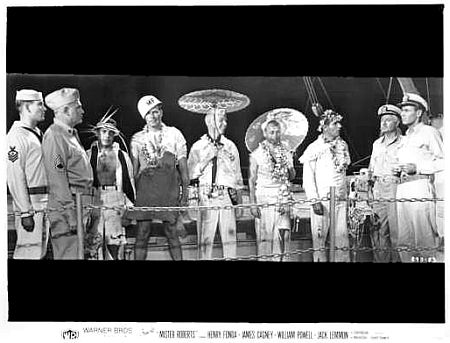

Right: Typical publicity still from Warner Bros. during the early CinemaScope era. Jack Warner may have had some bruised feelings after his short widescreen battle with Darryl Zanuck, but when he used CinemaScope he publicized it extensively. The only problem with Warner's CinemaScope pictures was the fact that they continued to use their own WarnerColor lab for several years, sending out the worst looking prints in the history of motion pictures. By the mid-50s, Warner's shut down their lab and went exclusively with Technicolor. The difference in the look of Warner product was very obvious, with the studio releasing some of the best looking films to come out of the Hollywood studios during the last decade and a half of dye transfer Technicolor. Right: Typical publicity still from Warner Bros. during the early CinemaScope era. Jack Warner may have had some bruised feelings after his short widescreen battle with Darryl Zanuck, but when he used CinemaScope he publicized it extensively. The only problem with Warner's CinemaScope pictures was the fact that they continued to use their own WarnerColor lab for several years, sending out the worst looking prints in the history of motion pictures. By the mid-50s, Warner's shut down their lab and went exclusively with Technicolor. The difference in the look of Warner product was very obvious, with the studio releasing some of the best looking films to come out of the Hollywood studios during the last decade and a half of dye transfer Technicolor.

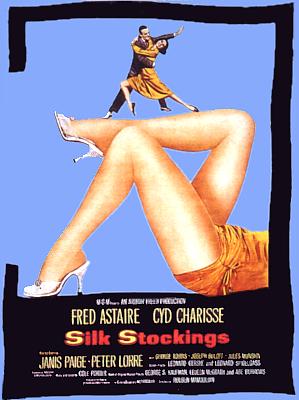

A bit of insanity from MGM: Silk Stockings, a widescreen remake of the classic Garbo comedy, Ninotchka, featured the Cole Porter tune "Stereophonic Sound" which said everyone wanted breathtaking CinemaScope, glorious Technicolor and stereophonic sound. Ironically, the Eastmancolor film was processed and printed by MGM's Metrocolor lab, and MGM used Perspecta optical sound on the vast majority of prints rather than real stereophonic sound. Cyd Charisse's legs were the real thing, however. This is evident in the MGM publicity still seen below. A bit of insanity from MGM: Silk Stockings, a widescreen remake of the classic Garbo comedy, Ninotchka, featured the Cole Porter tune "Stereophonic Sound" which said everyone wanted breathtaking CinemaScope, glorious Technicolor and stereophonic sound. Ironically, the Eastmancolor film was processed and printed by MGM's Metrocolor lab, and MGM used Perspecta optical sound on the vast majority of prints rather than real stereophonic sound. Cyd Charisse's legs were the real thing, however. This is evident in the MGM publicity still seen below.

Poster and still from the Setnik Collection

Cyd was no Garbo, but Garbo was no Cyd. New, larger size photo added by viewer demand. While the WideScreen Museum deals in technical subjects, it is necessary to include pictures as seen above in order to see how society dealt with these new technical wonders. And, besides that, the Curator happens to like them.

You are on Page 4 of

©1996 - 2006 The American WideScreen Museum

http://www.widescreenmuseum.com

Martin Hart, Curator |